- Chapter One - Radio Days

- Part Two - Early Career

- Part Three - On The Move

- Part Four - New York

- Part Five - Epilogue

“Act as if what you do makes a difference. It does.” –William James

Bob Hagen ca. 1939

In Akron Ohio, in 1935, you could sit in your living room and hear voices - voices from Akron, yes - but also voices from Cleveland, New York, Los Angeles, even London.

In homes where a few years earlier the evening's entertainment might have consisted of reading aloud or maybe a sing along, top-flight singers and comedians were suddenly available to entertain, all at the flick of a switch.

In 1935 in that city, into that of world voices traveling through the air, Robert Hagen

Hans and Bob Hagen ca. 1950

Like almost everyone else born that year, he grew up listening to the radio. He was captivated by the mighty news voices of the Second World War - Lowell Thomas, H.V. Kaltenborn, and Edward R. Murrow. He also delighted in the comedy of "Fibber Magee & Molly," "Amos & Andy" "Jack Benny" and others.

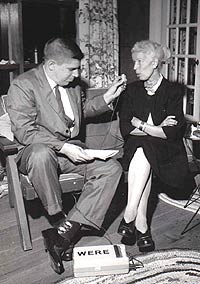

Bob and his mother Adeline

ca 1936

And he couldn’t get enough of sports on the radio, especially of his beloved Cleveland Indians But unlike almost everyone else born that year, Bob had a special fascination with radio that went far beyond just listening. It was to be a lifelong passion and his life’s work.

Akron was a union town—home of Firestone and Goodyear.

Bob’s father, Hans, was a postal clerk and president of the Akron local of the postal clerks’ union. He instilled in young Bob a passion for unions, the workingman and the underdog.

Bob’s mother, Adeline, was a homemaker whose influence helped shape Bob into the honest, loyal, and modest person he was.

Bob’s childhood was stable, filled with love, good home cooking and intense political discussions, something Bob always enjoyed. He learned to speak up for the little guy and to act on his principles. This would cause him some trouble more than once in his career.

Bob’s work ethic was evident early; he never missed a day of school. His lifelong love of sports also started in

Bob on the air at WKSU, December 1957

Bob graduated from Akron's Buchtel High School in 1953 and enrolled at nearby Kent State University—at that time still relatively obscure.

It was at Kent State that Bob got his first chance behind a microphone at WKSU, the college's 10-watt educational station. Bob did the news and called ball games. It was clear the young Hagen was talented and he was soon appointed chief announcer.

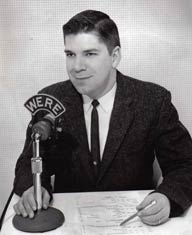

Bob Hagen's first publicity

photo from WHKK in 1958

In July 1956, Bob got his first professional job, a part-time gig in Akron’s WADC. Bob’s crisp, clear style was engaging and it got him an offer of full-time work at another Akron station WHKK.

While Bob's career was taking off, so was his love life. At Kent State, he met a fellow student named Marcheta. Keta loved Bob’s wit, good looks and great common sense. He loved her beauty and intelligence.

The two laughed at each other’s jokes, shared a passion for sports, and had a similar outlook on life. They fell in love and were married in 1958.

Bob was starting a family and needed an income commensurate with that responsibility.

He was ready to move to the big time. That meant Cleveland.

It seemed possible—Akron radio talent was frequently being called up to Cleveland. Alan Freed, the father of Rock and Roll radio, got his start in Akron before being called to the majors.

WADC's studios on State Street in Akron.

Bob wasn't far behind. In 1958, he was hired at WHK, one of the premier rock and roll stations in the country and

Bob and Keta

Realizing that the home of “Mad Daddy” might not be the best environment for doing serious news, Bob moved on to another Cleveland station with a more substantial commitment to news—WERE.

Bob at WERE in 1961

It was at WERE that Bob honed his skills a reporter, covering the sensational case of Sam Shepherd and scoring an exclusive interview with the former Axis Sally.

In 1962, AFTRA, the American Federation of Radio and Television Artists, tried to organize WERE. It was a tense, dramatic time. Word got out

Bob Hagen scored an exclusive interview with Mildred Gillers, the former "Axis Sally" in 1961

Bob paid the price for staying true to his values: he was fired.

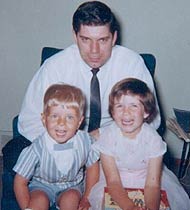

Bob with Ken and Laura

He was in no position to be out of a job. The young newsman was also a family man. Bob and Keta had been joined by their much-loved daughters Cheryl and Laura and son Kenneth.

But the blow was soon softened—he was immediately picked up by the biggest station in Cleveland, Westinghouse Broadcasting's KYW. While he continued to cover the routine stories that make up much of radio news, Bob was drawn to focus on the burgeoning civil rights movement in Cleveland.

Bob at KYW Cleveland, 1965

His contacts among civil rights leaders enabled Bob and KYW to provide superior coverage of the one of the most important issues of the day. In 1965, Bob was made news director.

Shortly after his promotion, Bob got caught up in one of the strangest episodes in radio history.

In 1955, through some convoluted maneuvering NBC had forced Westinghouse to trade its Philadelphia stations for NBC’s stations in Cleveland. In 1965, the FCC ruled that this trade was improper and the swap was ordered reversed. KYW and Bob were going to Philadelphia.

Bob Hagen at the relocated KYW,

the nation's second successful

all-news radio station.

Westinghouse had recently embarked on a risky radio experiment—an all-news format at 1010 WINS in New York, something critics said would never work. But it seemed to be working and they wanted to see if the experiment could be successfully repeated at KYW. Bob was put in charge of implementing the non-stop news wheel in Philly.

He pulled it off. KYW became the nation’s second successful all-news operation, with Bob Hagen as editor in chief.

Philadelphia was big. Chicago was bigger.

In 1967 Bob got a call to join the news department at WCFL, a Top 40 operation, owned by the Chicago Federation of Labor, of all things. This was an age when even rock and roll stations did news.

WCFL's large news department was considered one of the best in the Windy City.

Bob Hagen on the air at WCFL in 1967

One of Bob's first assignments for WCFL took him to Detroit - it was the summer of 1967 and the motor city was burning.

Bob was appointed news director of WCFL and led the station to a sweep of the Associated Press awards in 1970.

Chicago was big. New York was bigger.

AM Top 40 was starting to die out around 1970 as FM began to catch on. One of the first casualties was New York's WMCA, which usually ran a distant second to powerhouse WABC. WMCA management decided to launch an all-talk format with a heavy emphasis on news.

Bob was called to New York to help launch the effort. The talk format lasted…for a while.

The news commitment did not. Around Christmastime 1970 Bob found himself unemployed again.

And again, that didn't last long.

Bob on the air at WNEW AM and FM

There were plenty of opportunities for an accomplished radio newsman in New York at the time, and soon Bob found himself working at what many considered the premier newsroom in the city.

WNEW had an enormous news department—nearly 60 people—all the more remarkable considering that it was primarily a music station, but the news came on every hour on the hour.

The news on WNEW simulcast on the middle-of-the-road AM station and the

Bob in the WNEW newsroom

Bob anchored mornings and reported the news on WNEW through the 70's and into the 80's—tough, turbulent times in the city—with some highlights and plenty of lowlights.

Radio and radio news in particular were changing during these years. The idea of music stations with enormous news departments was falling out of favor.

WNEW staffers left and were not replaced. The hourly news was dropped from WNEW-FM. The news staff was further reduced. By 1986 the news department was little more than a shell—and after more than 15 years at WNEW, Bob was out.

Bob on the beat for WOR

It was becoming clear that if you wanted to do the news on the radio in the 1980's and beyond, you'd better be with a station that did the news on the radio and not much else.

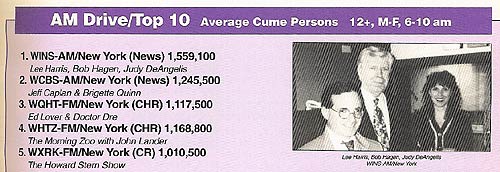

After a short stint at WOR, Bob found a new home at 1010 WINS.

It was exciting to be on the air at a station where there were no listeners sitting through the news to get to back to the music; the entire audience was tuning in specifically to hear the news.

Bob reported and anchored with equal skill. After almost forty years in the business, Bob was one of the best in the business. His news judgment was uncanny, his ability to communicate unparalleled and his style had long ago been perfected—his delivery was simultaneously conversational and authoritative. Listeners had the impression of hearing the news from a trusted friend—a friend with an incredible voice.

In 1993, 1010 WINS invited Bob to become a permanent part of the WINS morning anchor staff. He was now a member of the most listened to morning show in the entire United States. Millions of people woke up every morning to Bob and gave him “22 minutes” to find out what was happening. He’d come a long way from Akron. As Bob always done throughout his career, he did more than his job description required. At WINS, he was union shop steward. He wrote a manual on how to use the police scanners and was a mentor to junior members of the staff.

Bob on the balcony of his Manhattan apartment.

As Bob always done throughout his career, he did more than his job description required. At WINS, he was union shop steward. He wrote a manual on how to use the police scanners and was a mentor to junior members of the staff.

The hours were rough, as they had been for much of Bob's career. But living in a Manhattan high-rise less than a block from the 1010 WINS studios made it a little easier. He could stay up to a catch a ballgame and still make it to work at 4:10 in the morning.

Theodore Roosevelt once said, “Far and away the best prize that life offers is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.” Bob had achieved that prize and had done it with the admiration of his listeners and the respect of his colleagues.

Bob's last day on the air.

February 26, 1999

But the business was changing. It wasn't the same one Bob entered four decades earlier. He liked the new technology; he took to computers and the Internet with an enthusiasm and mastery unmatched by much younger colleagues. But he didn't like all the changes in the industry and he began to think about life beyond radio.

By now Keta had staked out a retirement home in Arizona with easy access to Cactus League baseball.

It was February 1999. A new millennium was approaching. It was time.

Bob joined Keta in Arizona. Free from the demands of his career, they could finally do the things other couples took for granted—go to movies, museums, and events together without the time constraints of the job.

A Phoenix station tried to lure Bob out of retirement to no avail. But Bob frequently weighed in on radio matters via the New York Radio Message Board on the Internet. A true newsman, he loved radio to the end.

Bob died at home, in Peoria, Arizona, on July 4, 2004.

His funeral was a celebration of his life and ended with a sing-along of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”